YOU HELPED US SAVE THE WETLAND

The campaign was successfully completed

We managed to raise funds to save 42 hectares of wetlands in agricultural land, thanks to 1076 donors, whom we thank.

You can find the Slovak campaign here - Slovak campaign.

In the last century, the Danubian lowland has changed a lot. Drainage canals were created to dry out the land and make room for farming. Many other changes contributed to biodiversity loss. Within just a few decades, we witnessed grasslands being ploughed, tree alleys being cut down, and their roots getting lost in immense fields of arable land. We witnessed drainings and ploughings of wetlands – places that are terribly missed in the ongoing climate crisis.

Our Regional Association for Nature Conservation and Sustainable Development (BROZ) has been working in Danubian lowland for 25 years.

We carried out multiple nature conservation projects in the vast fields of monocultures – unfortunately, the largest monocultures in Europe. Rapeseed and corn monocultures do not provide habitats for any of the animals or plants which were so common in the fields.

At the same time, any habitat restored in the area quickly abounds with life. Once discovered by insects or amphibians, the race for life begins. Literally.

The speed at which the new wetlands, thickets, and blooming strips get filled with life reveals the desperate need for these elements in the countryside.

A chance to save a wetland

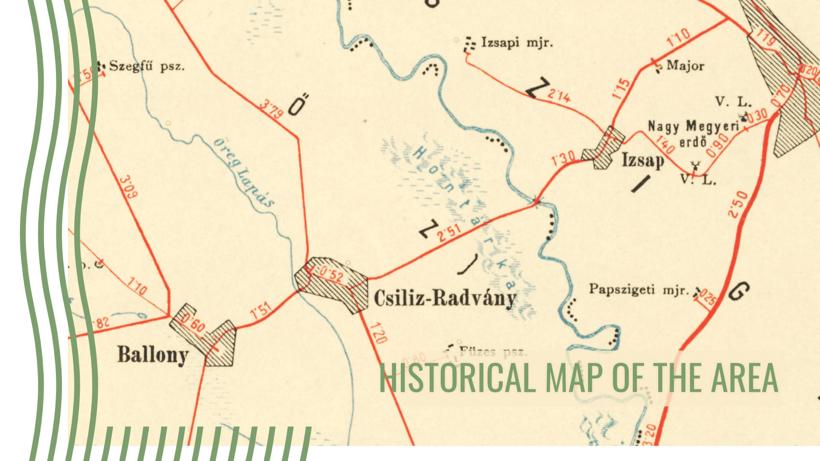

Recently, we got a chance to acquire a 42-ha area for nature conservation purposes. The land is adjacent to a Natura 2000 site and was originally part of a large wetland system – Čiližské močiare. However, the area currently does not fall under any protection, and therefore, farming is not restricted in any way. That means that until 2021, when BROZ leased the land, there had been a corn monoculture.

We were offered an option to purchase the land and we would like to take up this opportunity so that we could return these 42 ha of wetlands to the Danubian nature forever and with certainty.

A situation in the surrounding countryside

Reed-sedge swamps, home to Central European root vole (Microtus oeconomus mehelyi), are located near the future wetland. This little root vole is an endemic mammal, surviving in the area since the last glacial. It is a small, charismatic animal. It lives exclusively on wetlands and feeds on a wetland grass species – a sedge. Besides the Central European root vole, which would – without a doubt – spread to the new 42 ha wetland, thus increasing in numbers and stabilizing its population, the new wetland would become a suitable habitat for many other species, seeking refuge in an agricultural landscape.

Wetlands in an agricultural landscape are home to many amphibians all year round, many birds that come to hunt – e.g. herons, white storks, rare black storks, and others; as well as many dragonflies, and aquatic invertebrates, a foundation of the habitat’s food chain.

The drier zones are crucial for solitary insects, important pollinators. They play a substantial role in ecosystems, yet, the monocultures lack suitable spots for them to live. Moreover, biomass including the roots in unfarmed zones is needed for soil bacteria. Such zones serve as reservoirs – From here, the bacteria can spread to neighbouring fields after chemicals have been used, and improve the soil structure. Unfarmed zones become biodiversity islands, and the more there are and the closer they are to each other, the better for the restoration and health of our lands.

The closest wetland, called Bahno, is 4 km away as the crow flies –the distance that clearly shows the changes this wetland area has undergone. Bahno wetland covers only 15 ha.

To put it in perspective – the surrounding fields with intensive farming cover 50 – 100 ha.

The history and the present

In the 1960s, a nature reserve Čiližské močiare was planned in the area. Instead, after the big flood of 1965, the Rye Island (SK: Žitný ostrov, a part of the Danubian lowland) became massively drained and our plot was not an exception. In 1970, the work was completed and the area was connected to the large drainage system in the Danubian lowland. Sedge growths were bulldozed and drained, and the wetland was turned into arable land. However, as the zone lays lower in the terrain, parts of the area would be regularly flooded and, especially in wetter years, it was difficult to farm here.

This is quite a common situation in the Danubian lowland. Shallow wetlands appear on fields and attract birds, particularly in the spring. Unfortunately, as soon as the water is gone, the heavy machinery, ploughs, and sowing machines quickly plough the land, destroying the plover's nests and killing the life that the water had attracted.

Our plot is a natural lower-laying wetland that gets filled with rainwater. In addition, being a natural depression (landform sunken or depressed below the surrounding area), it gets filled with underground water, thus it is soaked most of the year.

Moreover, as we have already been carrying out our conservation efforts in a wider area for quite some time, we have modified the drainage system with weirs, so that the water levels can be adjusted and instead of draining, the canals can be used to flood certain zones. That allows us to bring the water back to the country during prolonged droughts and flood the area as necessary so that it becomes a reliable habitat for wetland species.

The easiest way to restore wetlands in an agricultural landscape is to make use of locations like this one – use places where the wetlands once used to be, and where no interventions, deep digs nor excavations are necessary. All we have to do is not fight nature – do not plough, do not drain. Nature will take care of the rest.

We do not want to protect nature at the expense of private owners and we do not want to limit the farmers.

To be able to guarantee wetland restoration and conservation, we need to have a long-term claim on the land. Ideally, we need to own it – that is the only way we can assure that a functional wetland will exist for decades, forever.

Climate change and wetland restoration

Extreme temperatures and droughts we have been experiencing in recent years are the heralds of escalating climate change. Wetlands are one of the most efficient mitigators of its negative impacts. They help us keep our landscape alive and habitable. Wetlands positively mitigate climate extremes, serving as large sponges that retain water in the countryside. Wetlands provide the surrounding arable land with enough water, thus improving the conditions for farming. That is why we are on good terms with our farmer neighbours. We do not fight, instead, we collaborate in wetland conservation to achieve prosperity for both nature and people in the Danubian lowland.